A Factless Autobiography: Debmalya Ray Choudhuri’s Tryst with Heteronyms and Life

© Debmalya Ray Choudhuri

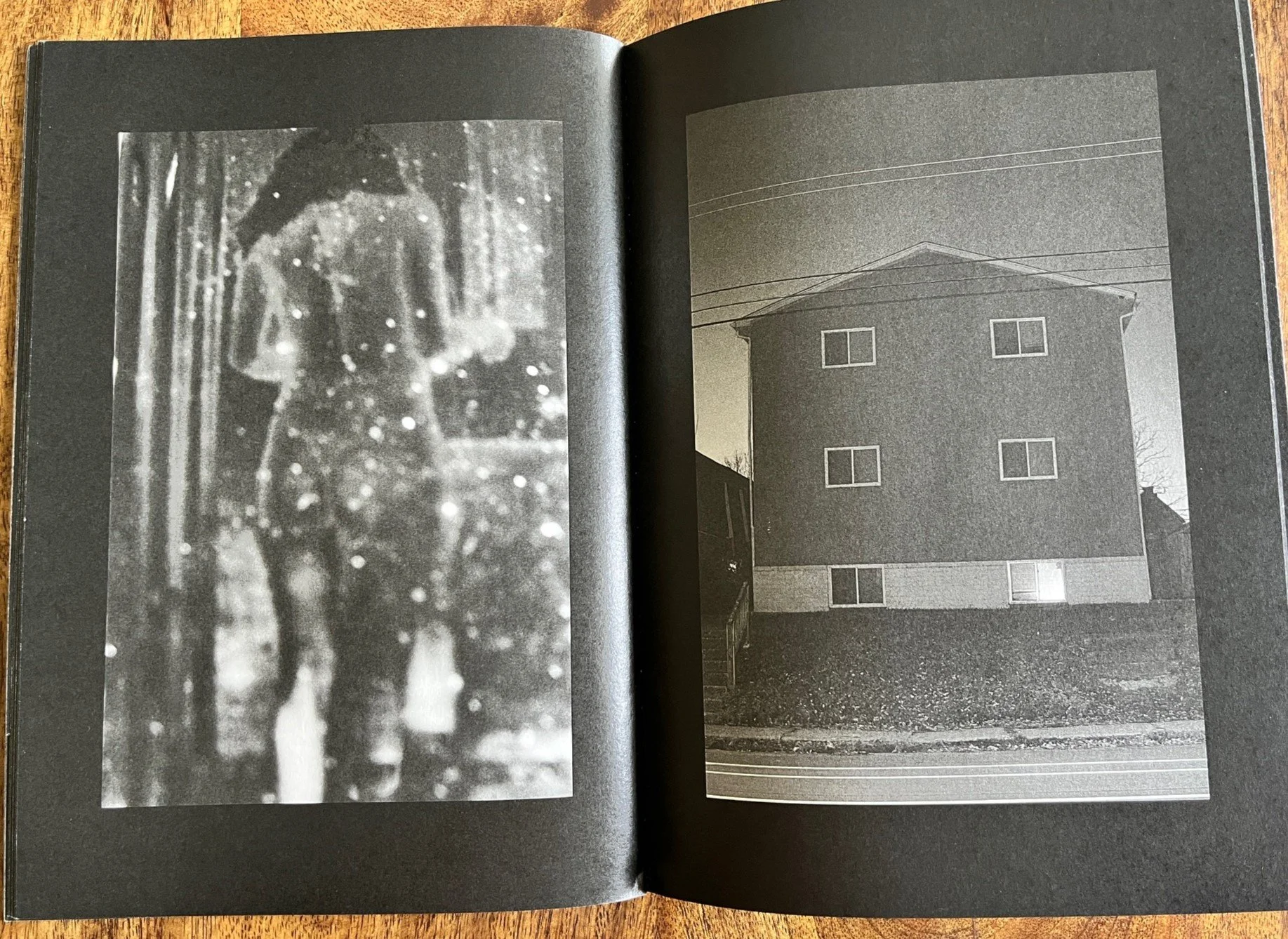

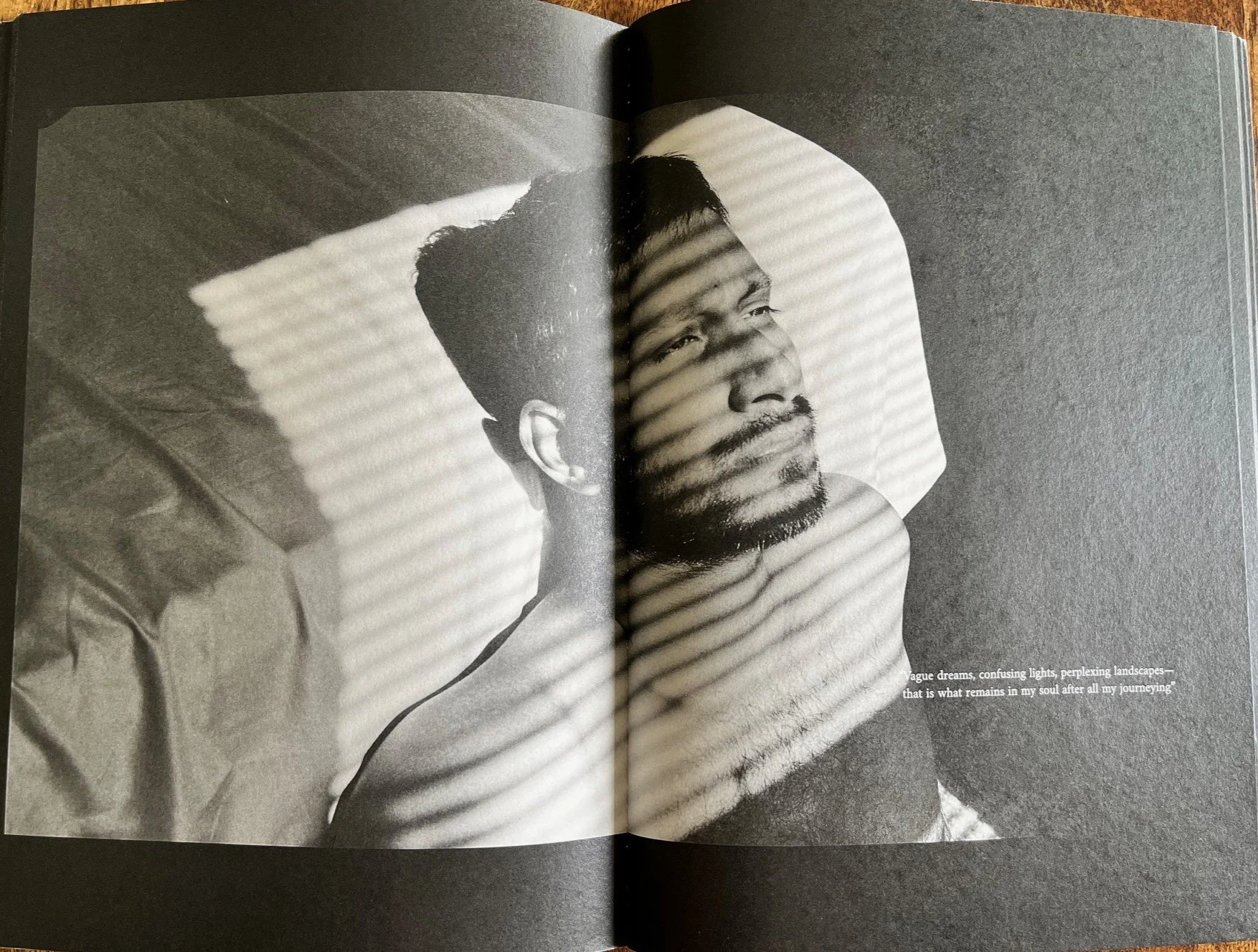

The silence in A Factless Autobiography is eerie and palpable in the absences hinted at. A ghostly quiet pervades the pages, unsettling at times, mysterious at other. The figures glaze the night with cosmic glow, conjuring landscapes where meaning seems amorphous, contorting to the touch but alive to possibilities, and nebulous like time, like space.

The images resonate with disconnection and anxiety even as they echo a longing to be subsumed in the larger cosmic riddle in an enchanting play of mystery in plain sight, of day, and night, gasping fluorescent.

Debmalya Ray Choudhuri’s book is as much about loss and living as it is about living the loss, some of it from consciously letting go, some from being let go, and the rest, from holding on to hold out.

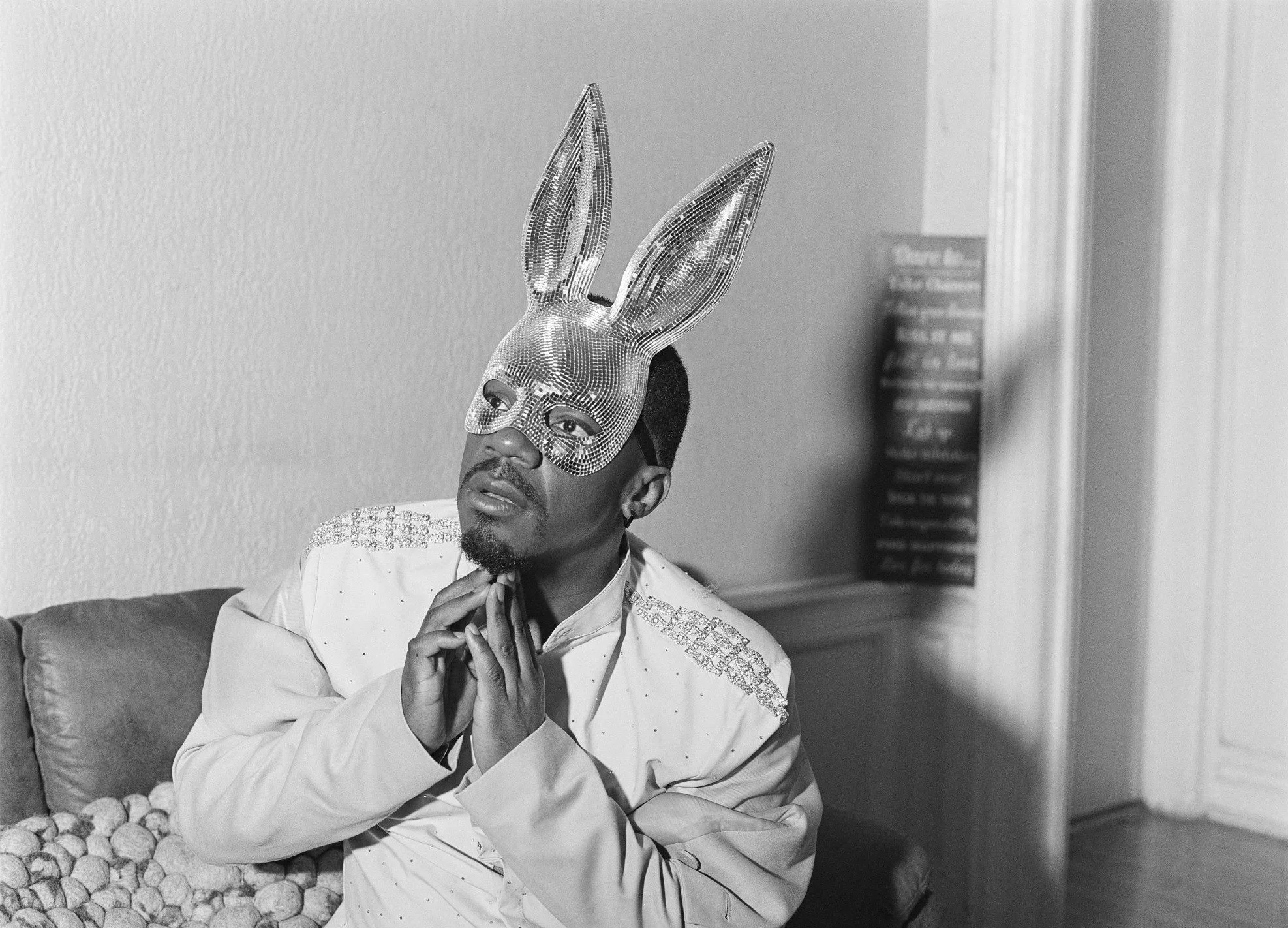

In A Factless Autobiography Debmalya treads “between the snapshot and the stage”, the here and now, and the projected – a partly performative rendering of what was and what could’ve been, all the while wrestling with his own identity in the context of self and in relation to others, slipping into multiple personas to navigate and make sense of the milieu he came to, New York, from the one he left behind, Kolkata.

Identity shapes and is shaped. It is as much a response to the need within as it is to factors without. To identify with people and place requires an identity that can be identified with by people and place. A Factless Autobiography is the search for one.

The search for identity transposes to a search for acceptance, and meaning. Identity ceases to be singular, becoming fluid and adopting personas that are distinct while deriving from each other, each heteronym (alter-ego) striving to bind the seeker with people, circumstances, and the place.

“We all have alter-egos, or perhaps several versions of the self, one that we hide from the world, one that is only meant for us, one which we are during the day, our nocturnal selves, and the ones that we project. Having said that, we have to embrace our authentic selves that may or may not have all these alter-egos.”

~ Debmalya Ray Choudhuri

© Debmalya Ray Choudhuri

Taking after Fernando Pessoa’s book of the same name, Debmalya sees himself in the ambiguities and uncertainties characterising Pessoa’s semi-heteronym, Bernardo Soares, particularly with Bernardo’s lament “no one knows anything for sure about the one who departed long ago, placing his hope in the false voyage, son of fog and indecision to come.”

It’s a voyage Debmalya strongly identifies with, having left his home, Kolkata, for New York years ago, at a “time of personal and political turmoil” in his life, a voyage he knows will not bring him the home he left behind, and to not keep going now is to cease existing beyond self, remembered by none, forgotten by all.

“Everyone I loved had forgotten me in the shade. No one knew when the last boat was. The post office had no information about the letter that nobody would ever write.”

- Fernando Pessoa in Book of Disquiet (formerly A Factless Autobiography).

I cannot shake off the feeling that the protagonists in Debmalya’s book reach for the elusive, and that the act of reaching to seek meaning imbues them with purpose even if toward uncertain outcomes.

There’s fear in their desire but you wouldn’t know, for, the deepest fear is outwardly calm as if awaiting the wave that must surely come, to draw them further away from shore to where still waters run deep, and silent – hastening their displacement toward dissolution, a battle the protagonists are enjoined so they may yet float free, even if alone and forgotten.

A Factless Autobiography is about remembrance, of beings and state of being. It derives from fear, of desire, and for desire, with impulses playing out in performative gestures that may yet come to a pass, in real – the alter-egos merely projections ahead of time, or not.

In my conversation with Debmalya, he ponders over if his performative self is a mutilation of his real self or if it is “another projection of mine” (that has not yet come to pass).

He speaks of using imagery to enact reality, using his camera to bring people and their stories in relation to his own, together in a moment of vulnerability, at times playing out as alter-egos, both as a shield to shelter from the world until there need for none and that to shelter the world from.

Join us ringside as Debmalya reflects on his search for trust and proximity, his struggle balancing desires and fears and negotiating the selves he constructs to navigate love, loss and longing in an increasingly complex world, told in images that live in whispers.

Anil Purohit: Centred on the life of Bernardo Soares, one of Fernando Pessoa’s alternate writing names, Pessoa introduced his lifetime project as “a factless autobiography”, later known as “The Book of Disquiet” after his death.

What are the parallels you drew between Pessoa’s fragmented construct of Bernardo Soares’ life and your own life that led you to use the same title as Pessoa’s for your book – A Factless Autobiography?

Debmalya Ray Choudhuri: There is an extract from one of the entries in The Book of Disquiet which ends:

“…no one knows anything for sure, about the one who departed long ago, placing his hope in the false voyage, son of the fog and indecision to come. I have a name among those who tarry, and that name is shadow, like everything.” (The Book of Disquiet, Entry No. 205).

This is what I keep coming back to. As I set sail for a foreign land, letting go of the chaos of my past and inner violence, I see myself in one of the many shadow selves that Pessoa constructed for himself.

This book is written mainly as diary entries—like a tree with several branches. My work, too, is focused on a personal diary that oscillates between the snapshot and the stage. Throughout Pessoa’s book and life, there is a persistent ambiguity surrounding the identity of the self and its relation to others. There is also a subtle provocation of thought around the ideas of love, loss, life, and death—elements that fascinated me and led me to adopt this name for my work.

~

Anil Purohit: Fernando Pessoa’s works transit through a multitude of literary personas, each distinct in character, exuding life of their own, likely different from his own except maybe for Bernardo Soares from “a factless autobiography”, of whom Pessoa writes in a letter to Adolfo Casais Monteiro, “He is a semi-heteronym because, his personality not being mine, it is notwithstanding not different from mine, only a mere mutilation of it,"

How do you read his “only a mere mutilation of it” in the context of the work in your book of the same name?

Debmalya Choudhuri: There is a certain violence associated with the word mutilation.

More subtly, I would say Bernardo was only a fragment of his own self, and he lived vicariously through his semi-heteronym. He may have been a real person, but his persona through these diary entries was a projection of Pessoa. This is where I, through adopting this name to my photographic work, play with the idea of what constitutes the self in photography and what the performative self is.

Is this mutilation of the real self or another projection of mine? The images of the self-vis-à-vis those of the others are another provocation of living the life of the other vicariously through images and fleeting encounters.

~

Anil Purohit: You speak of images in your book as a “token of gratitude for souls that have touched me and spirits that have re-kindled the flame within me”.

When seen in the light of the performative character in the work is there an element of your alter-ego, as with Pessoa, that you employ to express the “re-kindling” of the flame within you?

How important (or not) is alter-ego in constructing your visual expression?

Debmalya Choudhuri: Confronting the death of a beloved had cast doubt on the flame of life. While at a literal level, there is an element of performance in some of the portraits, the stories are of real people who re-enact desire and longing through the image.

I cannot say for certain if it is something they truly felt at that moment of vulnerability or something they wanted to project for the camera. The camera is only the device that brings us together. And all images are projections. Life and chance make things happen. And we add meaning to images later through the context under which we produced them.

Strangers who eventually become friends help me to find a purpose again. We all have alter-egos, or perhaps several versions of the self, one that we hide from the world, one that is only meant for us, one which we are during the day, our nocturnal selves, and the ones that we project. Having said that, we have to embrace our authentic selves that may or may not have all these alter-egos.

The elements of love, the search for trust and proximity to others, the desire for intimacy, and the slight fear of initial discomfort in chance encounters are part of my “alter-ego” that I employ for my practice. And these elements help me to keep going.

~

Anil Purohit: In the context of your work, and also generally, do you see it as inevitable for personal work to project a desired identity as opposed to a strictly lived one even as the projected identity derives heavily from the real one?

Debmalya Choudhuri: I think if one is invested in telling stories from a deeply personal position, you must live your truth, your authentic self. I don’t believe that one can separate projected identity from the one that is lived. How you choose to talk about it can surely be through a tableau, staged performances, acts, and gestures. All that becomes just different forms of how you want to narrate, but in the end, you must live the experience.

The problem or perhaps a blessing in disguise for photographs is that all images are in the end projections. What identity the reader projects onto the image may or may not be what the author has or had in mind in the first place, but once the work escapes the creator, identity, and in a larger form, the work itself is beyond the one who makes it.

© Debmalya Ray Choudhuri

Anil Purohit:

“A tenuous pane of glass Stands between me and life. However clearly I see and understand life, I cannot touch it.” - Pessoa

Do you see a contradiction here, as in ‘clearly seeing and understanding life’ should do away with the “tenuous pane of glass”?

How do you read the above in the context of the life you navigate within and without your work and the manner in which it shapes your approach to work in the book and beyond?

Debmalya Choudhuri: Life is full of contradictions, to put it mildly. I think the kind of mysterious and solitary life that Pessoa lived is seen through the weight of his words. It is as if you can see something clearly through a crystal-clear glass screen but fail to touch it. However, we must try to achieve that clarity or get close to it. I interpret it in a way that says we must persist in gaining clarity of life and who we are despite this pane of glass between life and ourselves.

Today, because of social media, the constant deluge of information, and the constant need to feel validated or to center oneself, we feel that we have a good understanding of ourselves and the world around us, but nothing is further than the truth. This is how I see this tenuous pane of glass today.

Photography is like life, filled with its inherent contradictions and tragedies too. Ofcourse at a commercial level, it is an unfair playing field, and most gestures only exist at a surface level of performative optics.

It is as if everyone knows about the disparities in art and society, but the glass keeps us separate from doing anything to change them. I try not to think about it so much, but I feel there is certain sadness in Pessoa’s words above: the inability to touch it. This I want to dispel and on the contrary use this pain (glass pane too) as way to see things and redefine my own position as a human being and artist in the world we live in.

~

Anil Purohit: In its simplest form, a camera on the sidelines is a witness to the world going by, of life and times of people and places, the exposures merely recording moments without necessarily shaping them always – the viewfinder more a voyeur than a participant.

At what point did you decide to invite the camera as a willing participant (or a protagonist) in A Factless Autobiography to aid and shape the dialogue with the viewer, and why?

Debmalya Choudhuri: I still think, at the end of the day, photography is voyeurism, either for the self or not. And there will always be power play here, one between the photographer and the subject, the image and the viewer, and the position of the photographer, both literally and otherwise.

One will have to own this and find ways in which the camera can shape a dialogue with those it photographs and the people who read the image. This understanding came through the numerous encounters I have had over the years and the stories I continue to share with those I meet. It was not a specific point in life but evolved through time.

~

Anil Purohit: As a sum total of possibilities it offers, a city can be simultaneously amorphous, shifting form to the seeking hand, remaining just out of reach and illusory to one soul, while also being definite, coherent, and real to another – a duality that is at once singular, at its core.

At one point when you ask “Who am I in this city of illusions?” what’re you hoping to find or realise if the city were to yield you an answer, assuming you’re looking for one?

Debmalya Choudhuri: Back then, when I might have wondered about this, it was more of a rhetorical question. Perhaps I was hoping to find an answer about my position in a foreign country, in a city that moves faster than the blink of an eye, but the answer lies in not having one.

© Debmalya Ray Choudhuri

Anil Purohit: A contiguous mood pervades the series of images, at once proximate yet faraway, alluding yet direct. They flit between hope and despair, dancing in the void between dusk and night.

In the gaze and limbs akimbo they seem to prevaricate in the face of reality yet not seeming to shy away. They seem to navigate an in-between unbeknownst to all except you and those appearing within the pages.

Tell us of the thought process you employed to string this visual narrative, the technique you brought in to manifest your vision, and the souls who flit between the pages – who they are and why they came to populate your ‘factless autobiography’ and the burdens you left behind on the pages.

Debmalya Choudhuri: That is a loaded one! Haha. This is the first chapter of a longer work I have developed over the years.

I am interested in portraying or experiencing a certain sense of intensity in the other and sharing vulnerability - in the end, that is what brings us closer together and makes us human. Yet, we are afraid to share this fragility of existence because we feel society will judge us. That is what made me adopt certain strategies to tell this story, and I was fascinated by the ambiguity of forms and darkness which becomes a thread in this work.

In the pages of this book, there were two protagonists who were my earliest friends in the US and people with whom I shared some deeply personal moments. I feel that the process was more of an unburdening of my own past back home, and making this book was the catharsis.

~

Anil Purohit: “Remain Free” – graffiti on a fence ringing in a building.

Do you see freedom as being untethered or being free from encumbrances, or both, and is it possible to be untethered from worldly affairs and be completely free from encumbrances and yet find meaning in and from life and material for art? As an artist how did you navigate these seeming contradictions in arriving at the sweet spot that finds spotlight in the world of art?

Debmalya Choudhuri: All art is political. And I think the ones that are personal yet have subliminal messages of our current times speak more to me. This work is also personal and political, even if people may or may not see the point.

“Remain Free” is to NOT be untethered from worldly affairs. Instead, it is to take responsibility for who we are as artists and human beings and to be free from the shackles of popular ideologies that can often manipulate you through language, visual or otherwise.

I don’t think I have arrived at any sweet spot, definitely not any spotlight in the art world, and all of this does not matter. What matters is how we use our voice, to be honest and authentic and tell stories that mean something to us and the world around us. It is a path filled with contradictions, and we must ask ourselves at every moment what can we do to “remain free”?

~

Anil Purohit: While most of us are born with an identity formed from a varying combination of religious, cultural, national, caste, and community characteristics among others, some of us will seek to make a new one that is persuasive of (and to) the milieu immediate to us, seeing and shaping our identity into one that the milieu derives value from, subsuming us into milieu’s own identity, in turn giving us its identity. Acceptance!

When you pose the question “Who am I in this city of illusions?” do you see it as a search for acceptance for who you are, at the risk of the search becoming self-perpetuating, where the identity is derived from the act of searching and not in its conclusion?

Debmalya Choudhuri: I agree. I think the molding of identities, especially when we are removed from our original background or context, this very process is often a subconscious one. Acceptance is not always a conscious effort or choice. For me when I asked this, I was more interested in the search for my space and position in a city of illusions. Illusions, well, because it is New York, and this is America. Pretty self-explanatory there.

The risk of the search becoming self-perpetuating will always be there if you are consciously trying to feel accepted or validated, but my purpose is something else. Always was.

© Debmalya Ray Choudhuri

Anil Purohit: In the context of your exploration of self, do you see illusion as the reality or do you see the reality as an illusion?

At what point do you see the crossover from one to another if at all?

Debmalya Choudhuri: I think when I talked about the illusion, I referred more to the physicality of the space I inhabit. Your reality cannot be an illusion, haha.

~

Anil Purohit: Desire is a want, simultaneously definite in form yet elusively formless, shifting shape over time, rarely sated yet infuriatingly demanding of ‘more’. It induces fear within and without, shaping destinies, of individuals and societies alike.

So when you mentioned elsewhere that photography has become a tool to explore ‘society’s economy of desire’, believing ‘that the common threads that connect all beings are our desires and fears that remain a subconscious part of us’, do you see fear as being derived from desire and if fear is the alchemy driving the transformation of desire into forms not necessarily desirous?

How do you harness them both to play out in your life, and work?

Debmalya Choudhuri: I am often reminded of a simple truth that a senior artist once told me: There is no life without desire, and to photograph is to desire. Fear without desire can also lead to madness, as you begin to feel contained and isolated.

Building on that truth, I believe that desire without fear becomes pure pleasure—but that does not fascinate me. It is the bridge between fear and desire that drives me to create. My work and life are deeply intertwined, and I hope to keep it that way. Both fear and desire are essential, not only in my work but throughout my practice.

My work, which engages people from all walks of life, is largely centered on themes of trauma, survival, and care. In this context, striking a balance between fear and desire becomes especially important.

Fear can arise from something as seemingly innocuous as a first encounter, a sense of mistrust, or meeting someone who has experienced deep difficulty or extremity. But once vulnerability is shared, a desire can emerge—to know the other person, to tell stories, to become friends or lovers.

So, for me, desire is often born from fear, and this fragility gives rise to different forms of longing—the photographic image being just one expression of that lure.

~

Anil Purohit: Tell us about your journey in bringing “A Factless Autobiography” to life with ephemere.?

Debmalya Choudhuri: I liked the vision of Ephemere and its work and supporting artists with a unique eye. I was following Anne on social media. Coincidentally, she was a student of Antoine d’Agata in Angkor Wat years ago, and Antoine was also my mentor and someone dear to me, but in a different situation.

It turned out to be a small world, and I pitched her the idea with a larger edit, and we went from there!

© Debmalya Ray Choudhuri

Anil Purohit: Kolkata is a long way from New York City, in spirit, character, topography, and outlook.

What of Kolkata did you have to leave behind so New York City could embrace you, and what of New York City did you eschew to retain the Kolkata in you?

Unless of course cities have alter-egos!

Debmalya Choudhuri: That is a tough one. I have always associated places with people and experiences with them. Leaving Kolkata was both a choice and a privilege. Being from a lower middle-class family, reveling in nostalgia for a glorious past could not be a way out. It was a time of both personal and political turmoil around us.

I left Kolkata for the first time at 21 and left India at 24. So, I was still very young. The Kolkata I left may have changed for me because the people who were once close no longer are. Some are dead. Maybe the houses are the same, the roads are the same, the structures and the general form are the same, but something inside me has changed, and that has changed my relationship with her.

New York, on the contrary, is a world apart. A relentless, unforgiving city, a city of blinding lights and illusions. This is not my home, no matter how much I want to feel a sense of proximity to those I photograph. I still try to keep going, with my desire. Having said that, I don’t want to renounce either Kolkata or New York, and I don’t think I can eschew one to embrace the other.

~

Anil Purohit: Where to from here?

Debmalya Choudhuri: Letting my desires, my curiosities, and my instincts guide me, being open to change, learning to look at old images again, and starting to work on my monograph, which is the ending (perhaps) to this long journey in America. Perhaps that would be my way of reconciling with the life that was.

© Debmalya Ray Choudhuri

~

Years ago on opening Somerset Maugham’s The Razor’s Edge, a book I returned to several times over the years, I paused at the book’s epigraph translated from the Katha Upanishad, an ancient philosophical-religious Sanskrit text of Hinduism, paraphrased thus –

“The sharp edge of a razor is difficult to pass over; thus the wise say the path to Salvation is hard.”

In original Sanskrit –

ksurasya dhârâ nisitâ duratyayâ; durgam pathas tat kavayo vadanti

And so began the story of Larry Darrell, an American pilot’s search for meaning in life after his traumatic experiences in WW1, seeking salvation from turbulence within, reluctant to conform to his milieu and adamant on seeking meaning to life elsewhere.

Underpinned by the delicate balance he had to negotiate between materialism and spirituality, two competing realities, the quest for salvation enjoined upon Larry the need to leave one place for another, for, where geographies equate to culture (materialistic), seeking a different culture (spiritual) necessitates a voyage in the hope that one can find and live one’s authentic self without the need for an alter-ego to balance out competing realities, neither of which one can forgo entirely if one is to survive in the host society.

The outcome of the voyage is rarely straightforward. A new geography and culture tolerant of one identity may not be easily accommodating of another, necessitating the adoption of a new heteronym to balance out the new competing reality, additional heteronyms if several realities.

It’s a realisation Debmalya shares about New York – “A relentless, unforgiving city, a city of blinding lights and illusions. This is not my home, no matter how much I want to feel a sense of proximity to those I photograph,” before continuing, “I still try to keep going, with my desire.”

“Ultimately, it is the desire, not the desired, that we love”

- Friedrich Nietzsche

Salvation is double-edged! There are times it lies more in the search than in its outcome.

~

Website: Anil Purohit

Inspired by the book of Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa, A Factless Autobiography is a deeply personal exploration of loss, desire, and the fragility of life by Kolkata-born artist Debmalya Ray Choudhuri. Through his experiences with the suicide of a lover, confrontations with tuberculosis, and grappling with queer identity as a South Asian immigrant in America, Choudhuri delves into the complex interplay of grief and melancholia. This visual project serves as a healing space for survivors of trauma and violence, amplifying anonymity and ambiguity to spark conversations on taboo topics like mental health, suicide, and LGBTQ+ experiences.