National Photography Month: Photo Studios, Albums and the Touch of Memory

Photo studio owner at the counter. Jaipur, India. © Khanjan Purohit

I remember the lane in Jaipur clearly. It was narrow and flanked by residencies and small businesses, one of which was a photo studio, clearly dating back to when film held sway.

Intrigued I stepped into the studio, past an empty counter with shelves showcasing studio portraits of people, advertising its services. A poster of Mithun Chakraborty, a Bollywood actor and disco dancing sensation from the Eighties, lent the studio a Bollywood touch. Only Kodak and Fujifilm rolls were missing from the shelves, a staple only a few years ago before digital crashed through film.

An open door led to a room lit by dim tube light. I went in looking for someone, anyone before finding the owner and his assistant in a tiny room bent over a Panasonic video camera running VHS tapes. It had clearly seen better days and so had the studio.

Studio backdrop. © Khanjan Purohit

A cloth stretching ceiling to floor hung from hooks at the back of the room, the painted landscape serving as a backdrop to studio portraits, a defining feature of Indian photo studios from decades ago, lending portraits a touch of picturesque settings exotic and largely out of reach to mainland India, and to many back in the day the only picturesque ‘escape’ from their immediate milieu.

Over the years I never tired of seeing these backdrops in person and in photos I came across. Each studio was engaged in varying degrees in out-competing its competitor with its own unique studio backdrop, often rivalling stage sets. It was an exciting time, streets enlivened by photo studios, their enchanting interiors and equipment inspiring awe in camera-illiterates; I was one of the tribe.

Before cameras became ubiquitous, photo studios ruled the roost, hiring out studio photographers for marriages, family and corporate events, and private family occasions.

I came to see Photo Studios as memory capsules of the city, prominently displaying in glass shelves facing the street a selection of framed studio photos of their customers – handsome men in suits, modest and demure ladies in saris or salwar kameez, and fetching couples, each advertising the look you could expect at the studio in question.

I found the studios to be magical places, usually located in the market and central to matrimonial fortunes of young men and women dragged by their parents to the photo studios for portraits transforming their marriageable-age children into cinema worthy personas worthy of being shared with matchmakers and families alike. Without skilled studio photographers and studio lighting I’ve little doubt the path to a successful match would’ve been a long and arduous one, in some cases a never ending one.

In time Photo studios came to hold my imagination in growing years. The trip to the studio, watching the studio photographer set up lights and handle camera equipment and film rolls, running my eye over photographs on display, seeking familiar faces while wondering about the stern or kindly strangers gazing back from frames before studiously following the photographer’s commands as he adjusted the pose and face tilts ahead of popping the flash, followed by an excited walk back home holding on to the receipt, wondering how the photos would turn out. It was an experience like few others.

Delhi was home to many photo studios, some acquiring a legendary reputation like Mahatta & Co., Prem Studio, and Ashoka Studio, places where they first made you feel good before making you look good in their studio prints.

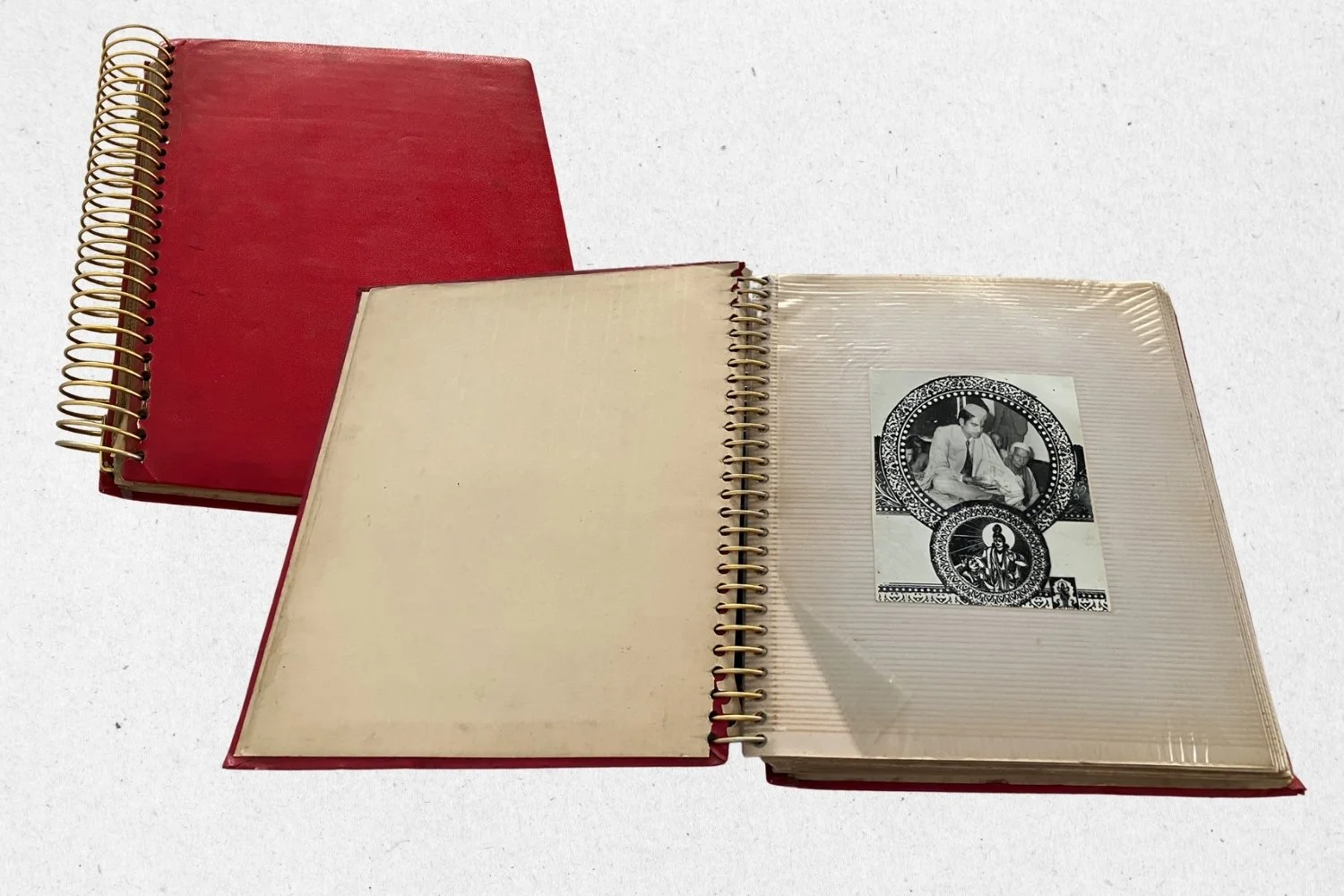

Mum & Dad’s Wedding Album. © Khanjan Purohit

Stepping into photo studios was like walking back time, a place where memories were minted in photo prints mounted with adhesives or silver corner-mounts on black paper and overlaid with butter paper in albums, the photo albums then handed over to families at once eager to make the trip to the studio to collect it and anxious about how the photos will have turned out.

It was not to last; the advent of digital, particularly smartphones, served to literally bring the “imaginative” curtains down.

Only a few now survive, the statuesque portraits giving way to questionable digital photos consigned to folders on hard drives. Well dressed men and women no longer peer out from glass-fronted shelves.

Only the family albums and stacks of family photos, from sittings in photo studios and events covered by studio photographers, remained to remind me of their time and mine long past, the memories a happy meeting between once carefree and innocent times and community camaraderie, ensuring many a nostalgic walk down the memory lane each time I thumb through them.

~

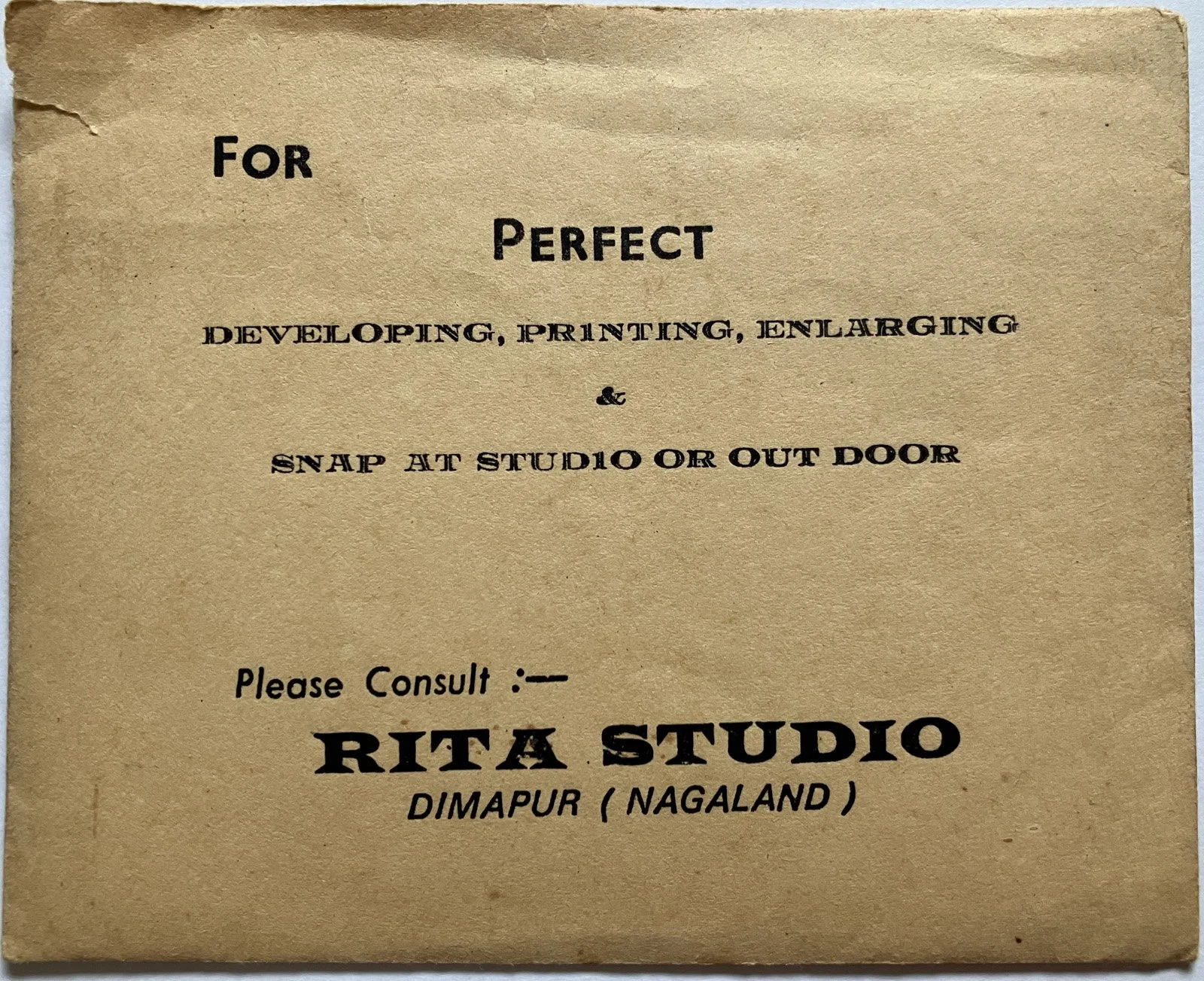

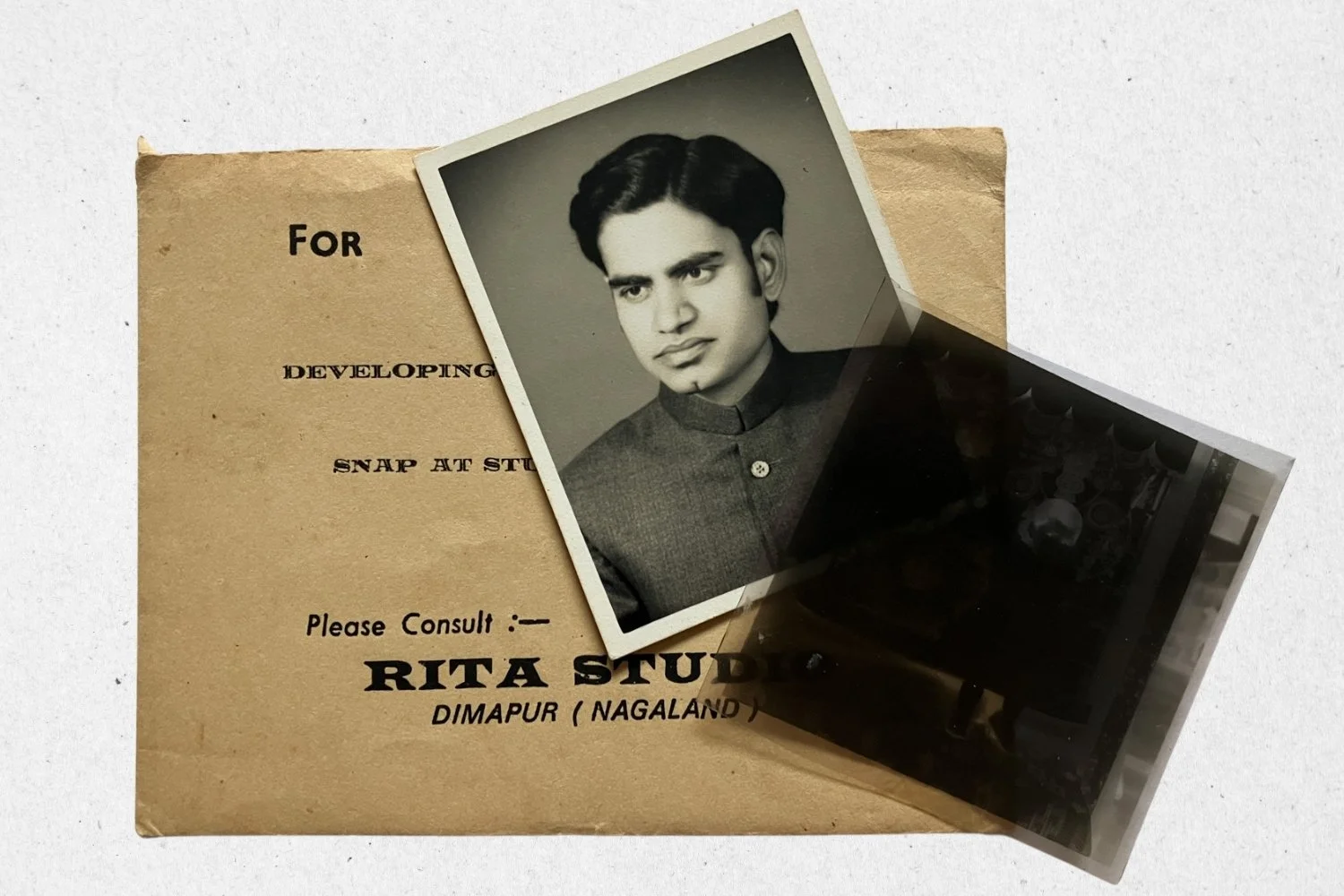

The envelope Rita Studio used to deliver negatives and photo prints. © Khanjan Purohit

The first time I saw the two small square yellow envelopes I was intrigued by the label – Rita Studio, Dimapur, Nagaland. A warm feeling suffused me as I opened them to find family photos and negatives.

Turning the envelopes over, I ran my fingers along the edges as if seeking to feel Dimapur, a faraway place whose air was the first I breathed decades ago, a city I remember nothing of but one I imagine most vividly about, eking out feelings for the city and people from the few b&w photo prints celebrating my first birthday in my father’s arms, oblivious to the merriment in my honour, my mother and relatives looking on.

Looking at the photos now I try and recreate the atmosphere and the bonhomie at the birthday party between the invitees, a mix of my relatives and my father’s friends and work colleagues in Dimapur, many of whom I would never see again. I wonder who they were and where they are now, the faces in the photos now forever a part of my life. At one year I doubt if I registered anything about the occasion, not knowing that decades on I would seek to register everything about the occasion from the few photos that survive in the album.

The photo from Dimapur of my father, Srikant, holding an year-old me while my mother and attendees look on, my birthday cake on the table, is one of the only half-dozen or so photos I have of my father and me in the same frame.

He died when I was still a teenager, long before cameras became common. No other photos survive from my brief time in Dimapur.

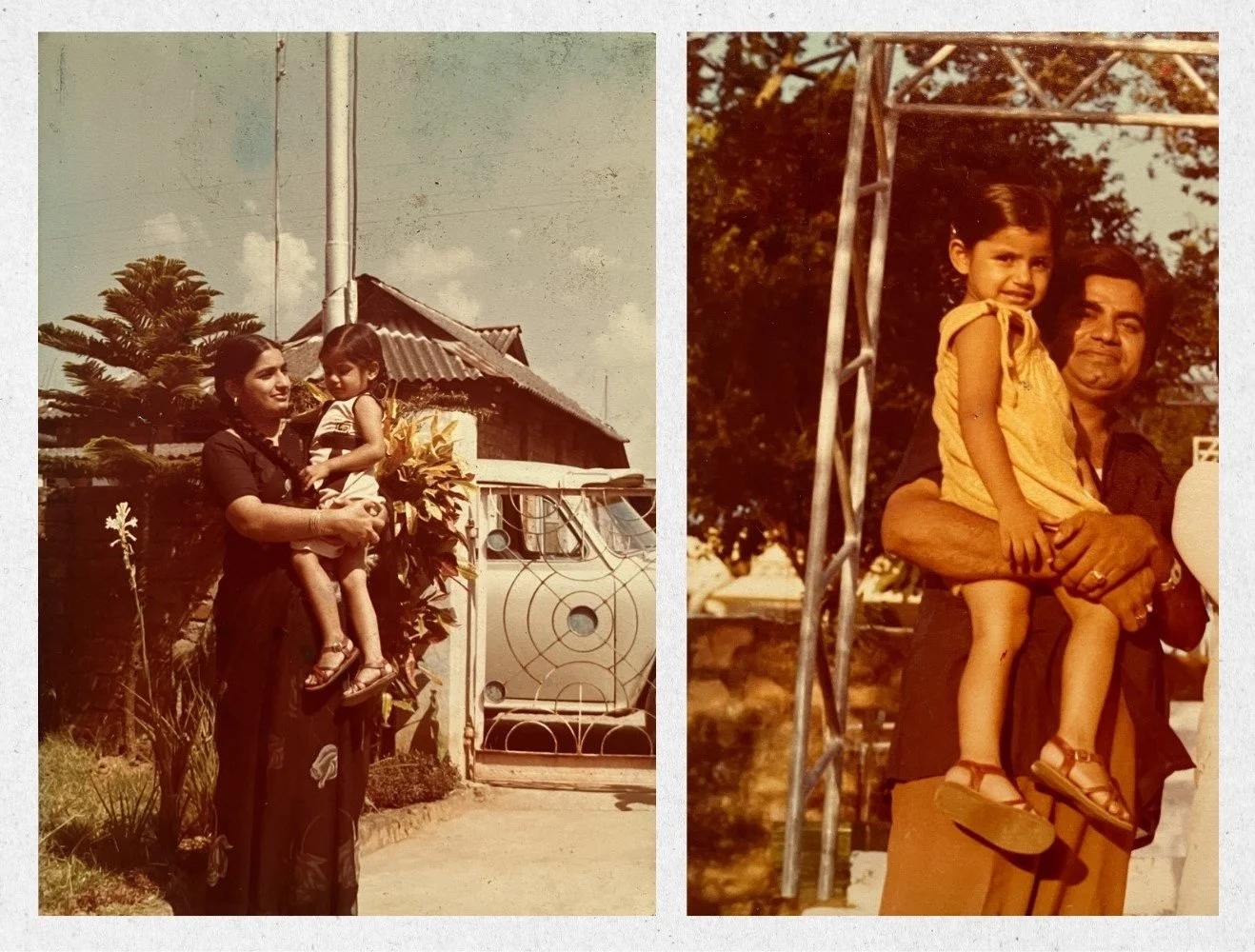

And fewer still from Guwahati, my father’s next posting. Just a couple of colour photos, one showing my mother holding me outside the compound of our cottage in Lachit Nagar, an Ambassador car parked out front, waiting for my father to arrive before stepping out for a spin around town with my uncle’s family visiting us at the time. The other records me in my father’s arms, the sun warm, matching my yellow dress, a golden hue permeating the scene.

Mum, Dad and Me in Guwahati. Ever ready for an outing. © Khanjan Purohit

Knowing these photos once passed through my father’s hands, I occasionally hold the prints in my hands, as I do others from his time, and imagine the scene beyond the frame, visualising my reaction on seeing him arrive where we were waiting and the likely conversation he must’ve had before spiriting us all around town.

As a tangible artefact, the photo print is the surviving bridge, spanning a continuity between my father and me, the anchor of a moment long past, but of import for the reason that he once had it as a memory of my mother and me, held it, his fingers tracing the edges before filing it away, to be looked at once in a while to relive family time from before, the photograph a hedge against time, and loss.

The B&W prints seem like physical extensions of the city, whose touch I carry with me like a living breathing thing. The prints connect me with my father who once held them.

Now I pore over the same photos he once parsed and arranged in neat piles, tracing the same edges, my touch lingering over it, over his, the photo print a mediator of continuity between us. The print is no longer now a mere image but a possession handed down, a memory heirloom carrying goodwill and remembrance down the years, particularly of a father I lost just as I was beginning to find my way about the world.

~

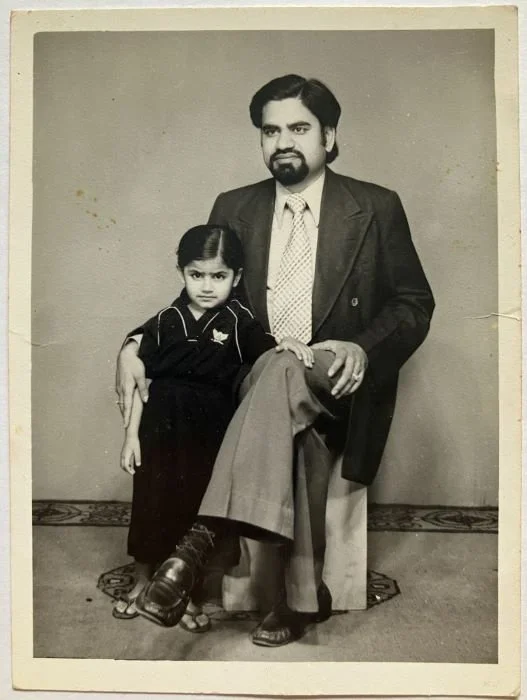

Posing with my father in a photo studio. Kanpur, India.

Through the eyes of my father, who may have effortlessly embraced heaven long back yet whose heart belongs to times when there was a romance that existed between the photographer & the image he hoped to create.

If he was talking to me today he would have reminisced about the patience involved in creating an image, the fragility of effort from the photographer’s end, the eagerness yet nervousness of waiting on what the final image would look like because not always did all the stars align, not always did the image turn out the way imagined.

He would have spoken of those times and touched upon these memories with the same delicacy with which I now hold his black and white photographs - it's hard to imagine those times gone by, but the twinkle in his eyes make me believe that those times were art themself.

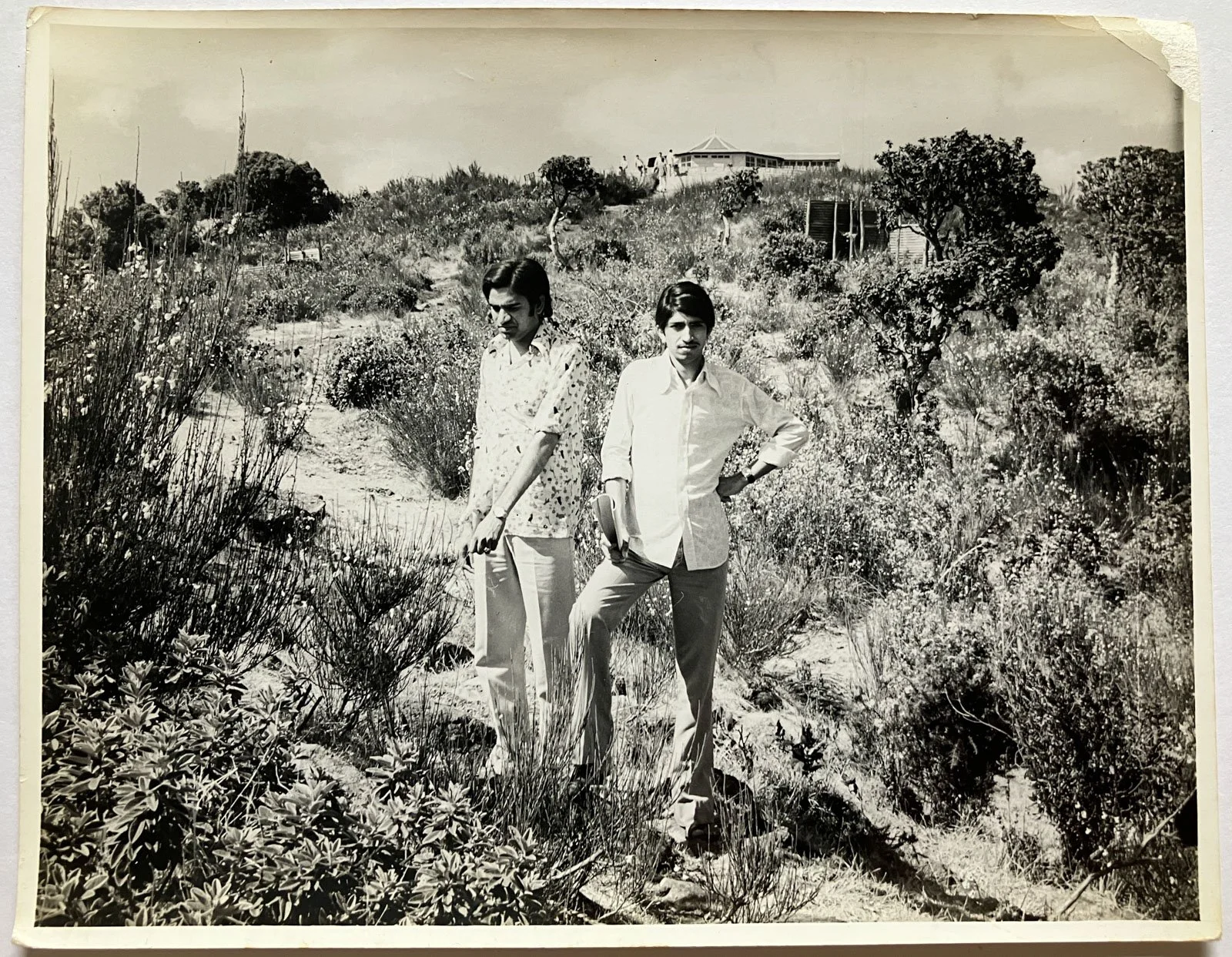

Dad on the left with his friend, Mr. Agnihotri, hand on waist. Dedeepetta Peak in the Nilgiris. 1976.

Passing time actively works to shape familial bonds, mediating the constant churning between personalities themselves changing with time, and shaping a memory prone to remembering the recent. If not for photos to remind of the bonds within family over time starting from early years, we’d be hard pressed to remember the evolving nature of familial bonds between members and of life back then that has little resemblance to the present.

Photos play a crucial role in reminding us of who and what we were years ago, ensuring a continuity to the personality we are now, a fact Sophie Gray reflects upon evocatively when looking through her old family albums.

~

Sophie Gray on leafing through memories and images in old family albums –

I always find it a strange experience to look back through old family albums. It’s almost as if I’m pulling back the curtains on another life; one that doesn’t belong to me, but someone else entirely. Memories and images often become so intertwined that it becomes impossible to untangle them, and though family photographs may omit certain truths, I believe they can also be a journey to finding who we are, or, perhaps more importantly, where we may go.

Sophie with her Dad. © Sophie Gray

When I look at these images, I feel a sense of connection to the parts of my family I didn’t have access to as a child. It allows me to form a deeper understanding of who they are as people, outside of the roles they played in my life.

Sophie with her Mum. © Sophie Gray

Emma Lewis, author of: ‘Photography — A Feminist History’, states that, ‘the family album is not simply a repository for memories; it is also their wellspring. It narrates family history, perpetuates family myths and can also heighten one’s feelings of belonging or exclusion.’ Viewed from this perspective, it’s interesting to me then which memories are deemed important enough to preserve and which ones are left behind.

Grandpa Jack reading a newspaper while cradling Sophie’s Mother. © Sophie Gray

Is it somehow irresponsible, or dishonest, to only present an idealised version of family life? It’s difficult to say, but I understand the desire to want to do so. I, too, feel a sense of responsibility to honour what has come before me and what will eventually be inherited by those who come after. If so much of who we are is shaped by our history, what do I want to be remembered for?

__________________

Sophie Gray is a photographer and writer working to explore and examine intimate themes within her work, hoping to find connection with, and resonate the complexities of human experiences.

IG: @sophiemgray22

~

As Sophie said, photos are connections with those appearing in the frames, a sentiment I can identify with and one which as I grow older, I return to ever more frequently. Over time I’ve now come to seek a connect not only with the people and occasions memorized in the frames but with the journey of the photograph, from who made the picture to how it came to be, via photo studios.

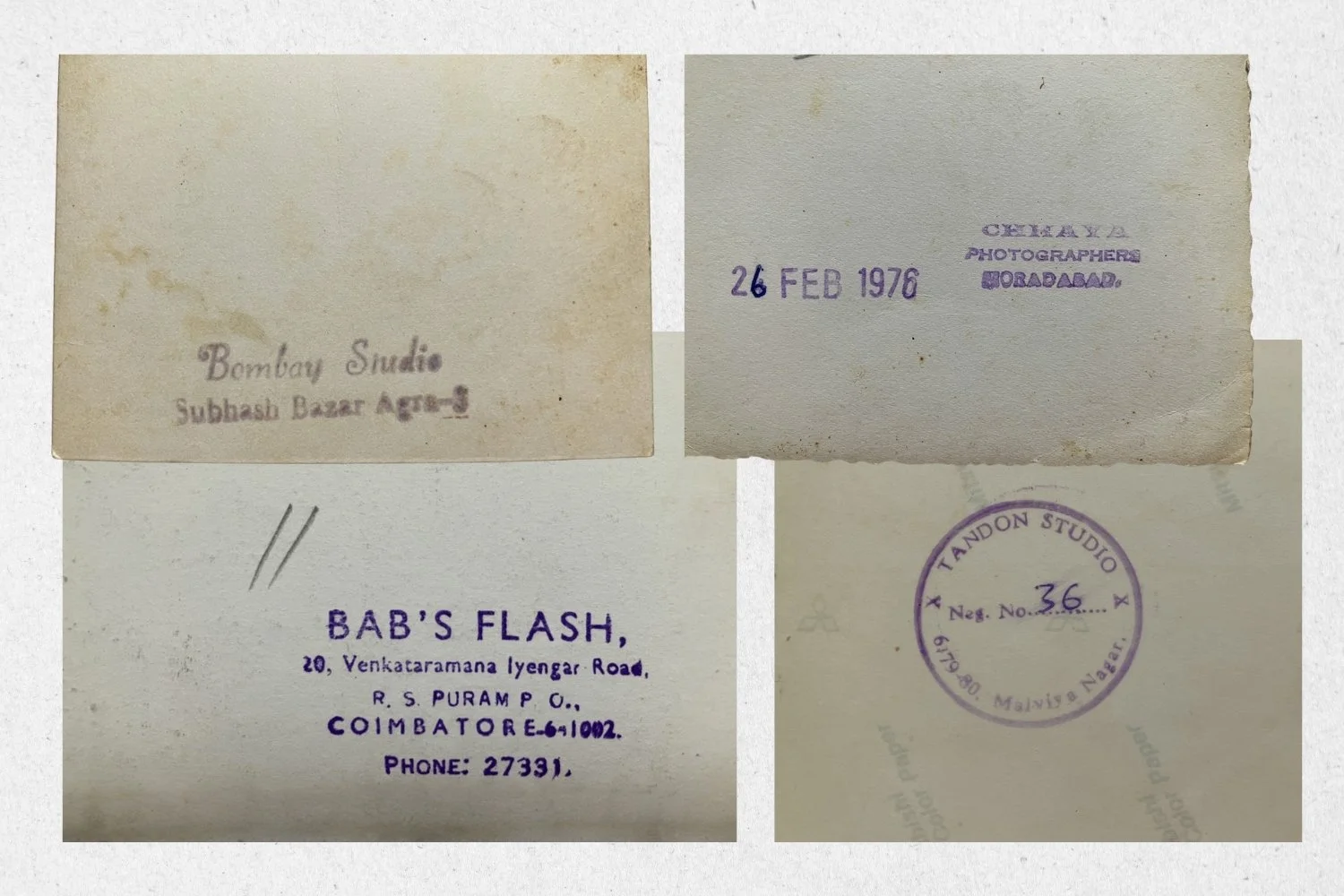

So as a habit I turn photos over to see where (photo studio) and when the photo was printed, and any caption describing the location and people featured in the image. Some photos in my family collection have names of studios marked behind, most do not. I pore over the names – Rita Studio (Dimapur), Chhaya Photographers (Moradabad), Bombay Studio (Subhash Nagar, Agra-3), Tandon Studio (Malviya Nagar, Delhi), Bab’s Flash (Coimbatore) and one from Albert Road (Allahabad) whose name is smudged.

I see photo studios as not mere locations but geographies in themselves, places my father, Srikant, likely visited to get the pictures developed and printed; their association however brief is now a place I harbour his memory, telling myself I’ll someday go take a look at the studio if it still survives in the character and state he saw it.

My Dad and a Negative showing me posing for a photo. © Khanjan Purohit

In drawing strength from memories of people who were once actively engaged with our lives, we turn the photo into a thread we seek to roll through every touch-point it traversed through our shared lives, effectively constructing its life story for, it has taken life for us and we live it in times of grief, longing, and joy, seeking comfort in the memory it refreshes, the bonds it reinforces, and the hopes it enlivens.

Farewell to the Humble Tailor is a poetic journey exploring valedictions, changes (metamorphoses) and the emotions associated with it through images and words.

Personal or else sentimental farewells and resigning from a vocational branch for good are communicating and become intertwined through a literal as well as metaphorical approach.

These subjects unfold around the simple action of transferring a car of sentimental value onto a cargo ship which then travels on inland waterways.

Photographs and Words: Judith Hornbogen

First Edition: 50 limited copies

Size: W21 x H14.8cm (A5)

Binding: Thread binding

Designer: April Seo

Printing: Tokyo, Japan

Year Published: 2025

Co-producer & Publisher: Anne Murayama, ephemere.